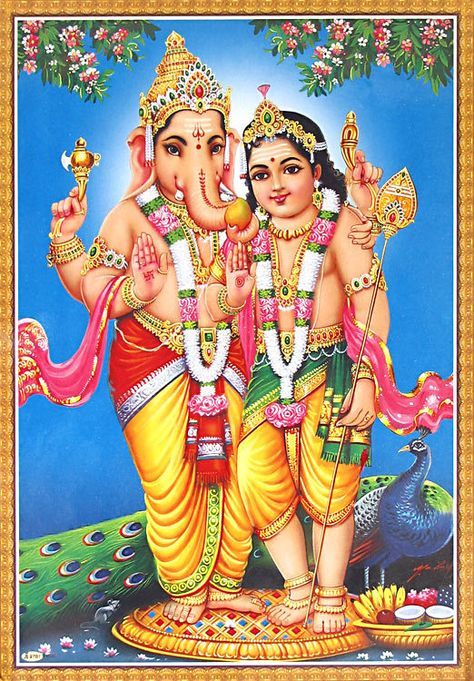

A friend traveling in India posted a picture of a deity on the dash of an autorickshaw. The mysterious deity that I identified using Google Lens was a young Murugan, son of Shiva and Parvati, and brother of the beloved Indian elephant deity Ganesha. It reminded me of a wonderful story I had heard about Murugan and Ganesh as children. The two siblings were somewhat opposites and I had retold this story at an innovation program in India to spotlight the power of thinking differently about obstacles and possibilities.

The story goes like this:

The God Shiva once presented the two boys with a single pomegranate and asked them who deserved it the most. Now Murugan, who was agile and athletic compared to the slow elephant-headed Ganesha, suggested that the prize should go to one who could get around the world thrice in the fastest time. It was a game Murugan chose so he could win. Ganesha shrugged with a look of amusement and said, okay, fine.

Murugan quickly jumped on his steed, a majestic peacock, and was off in a flash disappearing over the horizon. In a few minutes, he whizzed by, completing a round of the planet. Ganesha rose slowly, walked over to his parents, and began to circle them once, twice, and thrice. As he completed his rounds, he bowed to his parents just as a breathless Murugan touched down declaring triumphantly: I’ve won!

No you haven’t said Ganesha.

Huh? said a puzzled, Murugan, you’ve barely moved from the spot we started at.

Well, said Ganesha with a twinkle in his eyes, you went around the material world but I went around the world that matters — our divine parents. Let them decide who won.

Shiva and Parvati chuckled as they handed the pomegranate to Ganesha who promptly gave his red-faced brother half of the fruit.

The story illustrates many things. Murugan was fast and cleverly stacked the game to his advantage. But wise Ganesha flipped the game to his own advantage. He couldn’t beat Murugan in speed but he could outsmart him. He also played to his audience and the arbiters of the game – his parents. It wasn’t much of a contest as to what would please them the most.

I worked for two decades in innovation roles. There are often constraints and entrenched incumbents but the key to winning for upstarts is changing the game. Google took over the search industry from Yahoo not by adding links and features but by simplifying and improving the search. Apple beat Nokia and Blackberry by not adding buttons but expanding the screen. Netflix put Blockbuster out of business by eliminating the trip back and forth to the store and then making streaming movies available on demand. Examples abound of disruptive innovation that change the nature of the game and transform the world.

In India, the story I shared has great appeal because there is no shortage of barriers and constraints. People adopt a philosophy called jugaad that uses what is available, easy, or affordable to get the job done. India is now a leader in digital payments using mobile phones to transact purchases, bypassing the need for wads of cash, bank accounts, credit cards, and credit histories. With a large rural population, Indian hospitals turned to telemedicine and using local paraprofessionals who could run diagnoses and deliver treatments given by remote doctors in cities. Gandhi challenged the colonial British ban on selling Indian textiles (designed to make people buy British cloth) by encouraging people to spin their own fabric at home using a simple spinning wheel.

For those of us working to create change, we often face entrenched barriers and established institutions that wield great power and resources. To win we have to think about solutions differently. Much like wise Ganesha, it helps to consider alternatives that change the game and help us get at what matters most.

![Amazon.com: The Best of Enemies [DVD] : Taraji P. Henson, Sam Rockwell, Babou Ceesay, Anne Heche, Wes Bentley, Nick Searcy, Bruce McGill, Robin Bissell, Danny Strong, Fred Bernstein, Matt Berenson, Robin Bissell,](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71NmFd69wxL._SL1500_.jpg)