I am reflecting on an inspiring engagement in Portugal and lessons on peacemaking. The Ubuntu Fest gathering that I participated in was a celebration of Ubuntu and the African principles of connection and compassion (https://www.instagram.com/reel/CyRAXZEsjAq/?igshid=NzZhOTFlYzFmZQ==). IPAV, which runs the Ubuntu Leadership Academy, works in schools to develop empathy and service (https://academialideresubuntu.org/en/). In the midst of the conference about peace and unity, a horrific new war erupted in Israel/Gaza with the potential to turn the region and the wider world toward greater hurt, hate, and polarization.

In an active conflict, we may talk about securing peace but at best, we may secure a ceasefire. Peace is a state of being that is connected to a sense of security and freedom from fear. It is as much within ourselves as external. It has to be real. It is not achieved overnight. It has to be intentionally cultivated.

Peace is not really the opposite of war. Peacebuilding is the opposite of war. War destroys peace. Peacebuilding is creating peace. When conflicts emerge, we have failed to do the work of building peace – the work of building relationships and trust across people. Without this, we have separation and distrust. The creation of relationships is a slow process and as much an inner journey that shifts our worldview and feelings of separateness.

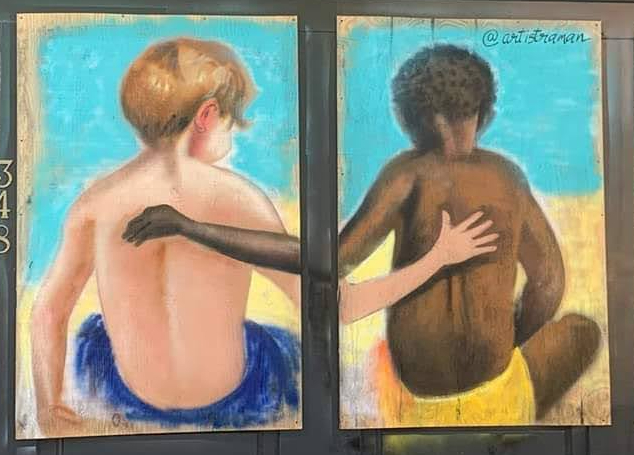

The Ubuntu Leadership Academy is planting these seeds of peace in young people in Portugal and across the world. By helping kids generate a sense of wellbeing, appreciate diversity, and enact service and compassion they are shaping the future. The evidence of this approach is also present in Scandinavia which made the journey from being poor and disconnected to prosperous, unified, and thriving through Folk Schools that developed young people to see themselves as part of a greater whole with others.

The war in Israel/Gaza is an example of the reverse – the failure of not just of politics and diplomacy but peacebuilding and relationship development. In the US too we are tumbling down the path of separation and laying the foundation for conflict. As polarization rises, we see social-emotional learning and DEI programs being removed rather than infused in schools. As personal wellbeing drops, people are retreating from community engagement despite the fact that community relationships create wellbeing and mutual commitment.

So, here we are, once again, at a pivotal time in history. The downhill road to conflict and the uphill path to peace and collective thriving diverge before us. As individuals, we can and must do what we can to nurture our own wellbeing and relationships but we need systemic action – in schools, in communities – to shift our collective states. There is awareness of this in places like Portugal that have embraced the idea of Ubuntu in schools and developing these capabilities in the next generation. Portugal, a small nation, has chosen to be open and welcoming rather than closed and fearful. The impact is evident in the level of kindness we encountered everywhere in interactions with people in the country. It is clear that these attributes are part of the DNA of society. Portugal has emerged as one of the most popular destinations not only for its sunny weather, but its sunny disposition. It reflects in so many ways what many of us are seeking.

There is an old Sufi story of a man who was traveling in search of a better place to live. Traveling to a new city, he approached an old man in the marketplace and asked – How are people here? The man asked in return – How are the people where you come from? The traveler shook his head and said: They are rude, angry, and hateful. Ah, said the old man, it is the same here. On another day, another traveler, also in search of a new home, approached the old man and asked – How are people here? The man once again asked in return – How are the people where you come from? The traveler said: They are kind, loving, and generous. Ah, said the old man, it is just the same here.

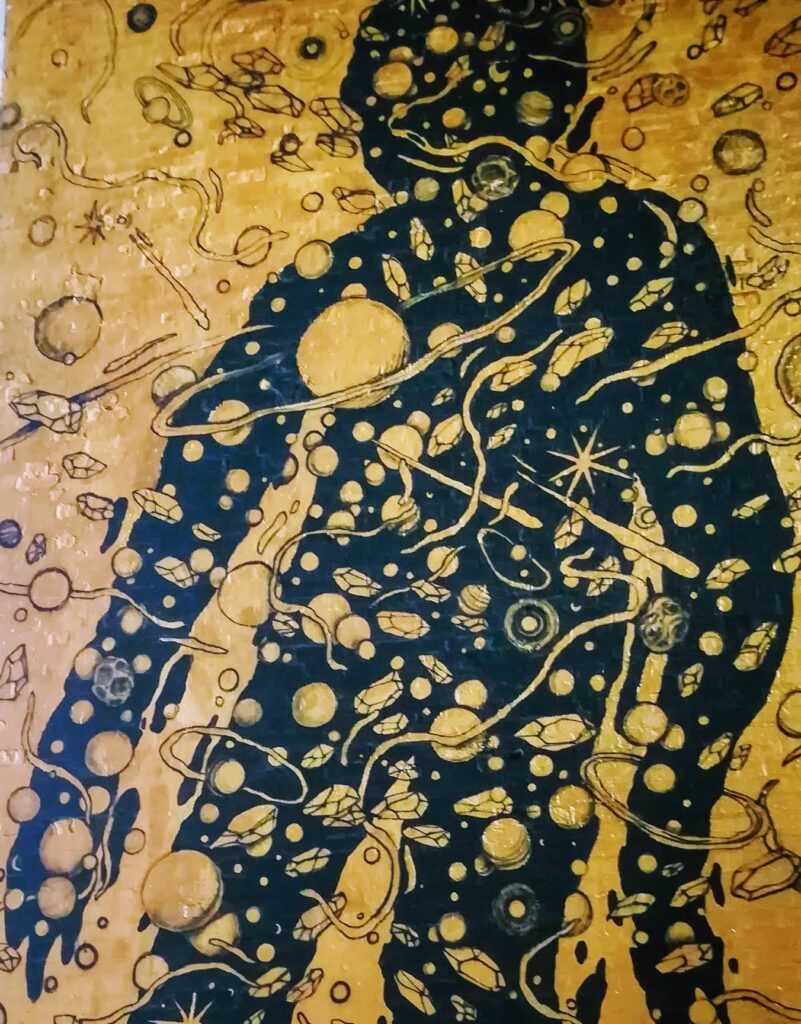

The story indicates we can’t escape what we carry with us, within us. We have to be the peace we seek. The world is an expression of ourselves. In South Africa, the home of Ubuntu, Mandela said that you can’t change society unless you first change yourself. Mother Teresa said, If we have no peace it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.

The conflicts in the world are a reminder that our futures are bound together. And that the path to peace in the external world lies within us all. Love wins or we all lose.