Experiencing pain and suffering are a salient part of being human. We have all have been served with hardships and loss, some of us to a far greater degree than others. Pain experienced repeatedly and left to fester becomes embedded trauma. Trauma unhealed metastasises and is triggered again and again. In this pattern, a lot depends not just on what happens to us, but how we process and heal the hurt. I had an ‘aha‘ about our response to suffering reading the framing of The Book of Job by Stephen Mitchell. It cast that Biblical story in a new light for me.

In this telling, Job is a righteous and successful man. He has a big family, good health, a good reputation, and a prosperous business. One day it all changes. His business fail, his children die one after the other, he loses his health and is reduced to being destitute, living by the side of the road, sick and covered in sores. His former friends passing by accuse him of having done something evil in order to be punished thus. Job knew he hadn’t done anything to deserve his lot and lamented endlessly to God. One day, God takes him up to heaven where he sees for a moment with God’s eye. In a flash, he takes in the breath of the universe and its many interlinked connections that ripple across the span of people, place, and time. It all makes sense. Job bows down with acceptance and humility, Who was I to doubt?

This story recognizes that we don’t know why bad things happen to good people and we may never know what ripples forth in the grand scheme of things. It offers that there is meaning beyond what we can see and our job is to accept what has happened with grace. This acceptance is a way to release the mental suffering that can eat us up on the inside.

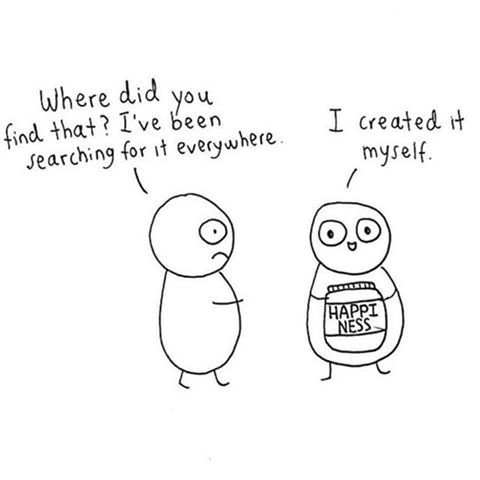

Another powerful reframe is the story of Viktor Frankl, who wrote Man’s Search for Meaning. As a young Jewish psychiatrist from Austria, he was imprisoned by the Nazis in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Trapped in this horrific environment — with brutal labor, bitter cold, starvation rations, beatings, and the constant threat of being killed — there was little reason to feel anything but deep suffering, grief, and despair. But Frankl flipped this script of hopelessness. He decided that he would use the little power he had to make a difference. He chose to comfort his fellow prisoners, help them where he could, and share the little food he had with those who needed it more desperately. Over time, he felt his power grow until he felt more powerful than his captors. He said: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

What Frankl discovered — the philosophy he called logotherapy — was that we can’t necessarily control what happens to us but we can choose how we respond. The Buddha also focused on this very idea. He said, I come to teach one thing and one thing only. The nature of suffering, and the end to suffering.

If we don’t transform this suffering, we can retreat in despair, become defeated, or grow angry and bitter, weaponizing the pain for attacks we launch against ourselves and others. We see this pattern play out with some powerful people in business and politics who do enormous damage as a result of the inner hurt they have experienced, often as children.

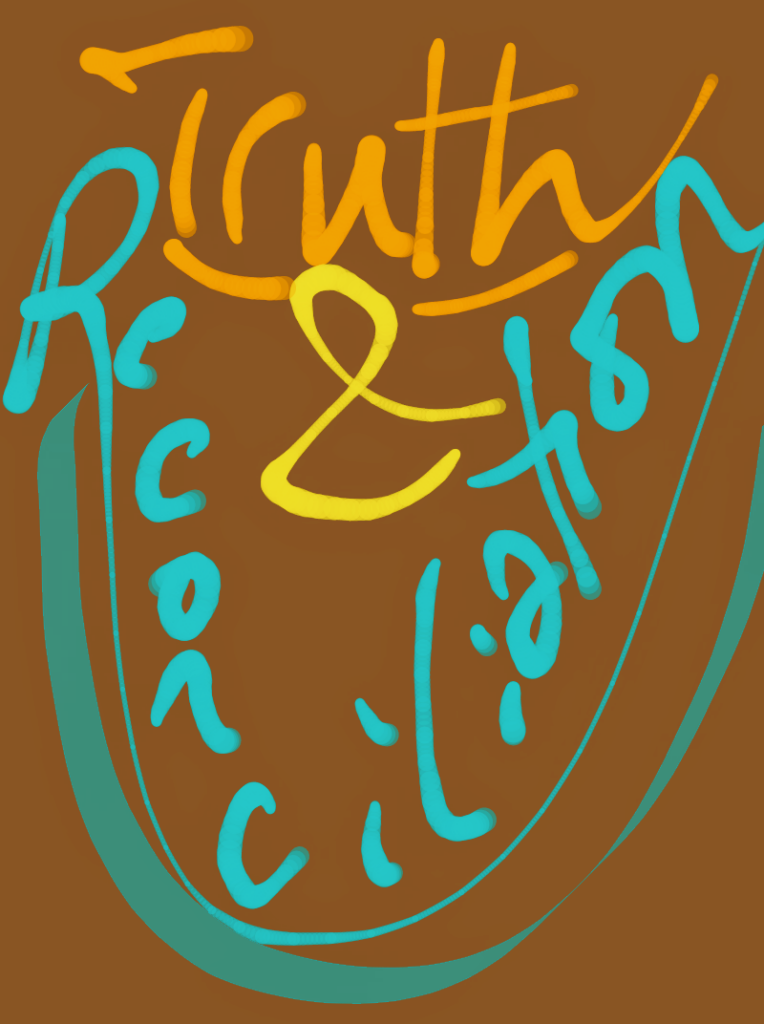

At the same time, people like Mandela, MLK, and Gandhi are leaders who create great change precisely because they have suffered great ills and injustice (I will explore this further in future posts). Mandela wrote, “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.”

In all these examples of engaging hardship — with acceptance, resilience, compassion, or transformation — we see that the hinge that swings us backward or forward is the internal meaning we make of suffering. How we process hurt and the story we create around it for ourselves changes everything. The Buddha, in his parable of the Two Arrows, asks: If you were shot by an arrow, would it hurt. The listener answers, yes, it would. And, continued the Buddha, if you were shot a second time, would it not hurt even more. The answer is, of course it would! The Buddha then says, the first arrow is the thing that hits us from the outside. The second arrow is the one we shoot at ourselves in response to the first arrow. It is the suffering we create for ourselves with our response of anger, fear, hurt, or despair. And, it can become a far more grievous wound. This is a lesson I have to continually remind myself about when bad things happen and I reach quickly, automatically, and unconsciously for the second arrow.

So, the key is choosing not to fire the second arrow but to turn our suffering into an instrument for engaging hurt and injustice with compassion and courage. But how? This transformative practice is not easy but possible. We will explore some spiritual ideas and practices for that in a future Spiritual Sushi post. For now, what is your experience with suffering? What enables you to release or transform it?

Related Posts:

Walking in the Garden of Forgiveness

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/walking-garden-forgiveness-lyndon-rego/

Why Fore-giveness is better than Forgiveness

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-fore-giveness-better-than-forgiveness-lyndon-rego/

Healing the Heart of America

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/healing-heart-america-lyndon-rego/